The Campaign of 1761 and the taking of

Schweidnitz by Laudon on

1st October 1761

By the beginning of 1761 exhaustion had set in among the protagonists in the war, and there was a growing desire for peace. Attempts to begin serious negotiations failed, and the war continued.

Development of the Campaign

Initially Maria Theresa kept the largest Austrian force under Feldmarschall Daun (89,000 men) in Saxony in

response to requests from Versailles to cover the right flank of a French army which it was promised would

advance from the Main (the French had promised that early in May an army of 100,000 under Soubise would advance from the Lower

Rhine, and a second army of 70-80,000 under de Broglie would advance from the Main).

In Silesia in mid-April 41,000 Austrians under

Om 7th May Vienna received a note from St. Petersburg stating the Russian intention to assemble an army of 70,000 men at Posen in early June, this was to march to Silesia and join Laudon (the initial Russian plan for 1761 had been to besiege and take Colberg in Pomerania, then to advance to the Lower Oder and besiege either Stettin or Küstrin; a smaller corps would go to Silesia to reinforce Laudon). The Russians did attach various conditions to the proposals, but the Austrians accepted the plan at once. On 13th May Maria Theresa wrote to Daun stating her intention to make the major effort of the campaign in Silesia. Experience had shown that not too much could be expected from cooperation with Russian forces, but this time things might be different in view of the overall situation.

The reasons she gave in the letter for the change in the Russian plan were that Pomerania and the Neumark were exhausted and could no longer supply food or money, and as such a Russian army besieging Stettin or Küstrin would have supply problems, also the Russian generals felt that a siege in that area would be too risky a venture and consequently they would rather operate in Silesai, and finally on 2nd April the Prussians had signed a commercial and friendship treaty in Constantinople which led the Russians to believe that the Turks might soon go to war with them. The empress felt that there may be a risk of war against Austria as well, so it was important to make a decisive effort to recover all or much of Silesia and bring Prussia to its knees.

The treaty with the Turks, which Frederick had hoped would bring Prussia some advantage in the war, in fact had the opposite effect.

The Austrians planned to leave as many troops in Saxony as the Prussians under Prince Henry had there, this would require 40,000 men (not including the garrison of Dresden the Reichsarmee or the light troops); the rest would be available for Silesia. Of the 70,000 line and 12,300 troops avalable to Daun at this time (he had already sent some reinforcements to Laudon at the beginning of May) 30,000 line and 6,000 light troops could be sent to Silesia. Beginning on May 5th troops were sent to Zittau in the Lausitz, where a force of 30,000 was to be assembled; its purpose was to mislead Frederick as to the Coalition intentions, and it would be able to move quickly to assist either Laudon or the army in Saxony as necessary. Further, on the assumption that the Russians would cross the Oder at Frankurt and then march southwards down the left bank on their way to Silesia, the forces at Zittau would be able to unite with them at an early stage. Some of the 30,000 troops were in fact sent on to Laudon immediately in response to his calls for reinforcements; further units came to his army from Bohemia and Moravia. As a result, on 20th May the Austrians had around 20,000 men at Zittau, and Laudon had 58,500, with detachments at Trautenau, Silberg, Wartha, at Wüste-Geirsdorf south of Waldenburg, one some distance to the east at Kunzendorf (south of Neustadt in Upper Silesia), with the main body around Dittersbach (5km. west of Braunau in Bohemia north-west of the County of Glatz). The Prussians had a detachment of 12,800 under Generallieutenant von der Goltz at Glogau on the Oder, the main body of 48,000 under the King was in a line from Zeisberg (west of Freyburg)in the west to Lauterbach (9.4km. north-east of Reichenbach) in the east, in various positions and with some troops in quarters. The positions of the two armies remained essentially the same (except for some very minor adjustments) until June 22nd; during this period the two sides were content to observe one another, and the only fighting consisted of skirmishes between outposts.

The Russian deployment for the 1761 campaign was rather slower than originally planned. They had promised the Austrians that they would have 30,000 men at Posen in early May with the main army concentrated there by the end of the month, but by the beginning of June only 10,000 had arrived there. The concentration of the main forces which were in winter quarters east of the Vistula began on 12th May, and only on the 21st were they in the prepared camps on the left bank of the Vistula. The troops marched between 26th May and 2nd June, and by 3rd June there were 24-25,000 men at Posen. The main army was concentrated at Posen by 19th June, and remained there until the march to Silesia began on the 26th (the army which did march to Silesia included some 50,000 combatants). Iniitially the Russians headed towards Glogau, intending to mislead the Prussians as to coalition intentions and to draw forces away from Frederick`s main body, the army was eventually to cross the Oder and unite with the Austrians in the area of Breslau.

The approach of Russian forces began to affect the situation in Silesia during June, and on June 26th Frederick strengthened the detachment under von der Goltz at Glogau, bringing it to some 20,000 men, with the intention of sending it to attack the Russians gathering at Posen. The force was to march on 28th June, but von der Goltz fell ill and died shortly after and was replaced by General der Cavalerie von Ziethen, who began the advance on the 29th. On the 30th he clashed with the Russian advance guard at Kosten on the Obra. Ziethen marched from Kosten to Storchnest to the south on July 2nd, here he was unable to get any information about enemy movements for some days on account of the superior Russian light cavalry.

Laudon resumed operations once the Russians began their advance towards the Oder. He brought in the reinforcement he had been promised, such that by July 17th his army stood at 77,400 men. On 4th July Laudon sent forward a detachment of 5,000 light troops and this prompted Frederick to concentrate his army. He sent orders shortly after to Ziethen to move to Breslau, and when the detachment arrived there on the 12th Frederick ordered Generalmajor von Knobloch to cover Breslau with 13 battalions and 21 squadrons, the remaining 11 battalions and 26 squadrons under Ziethen were to be ready to join the King`s army if required. The Russians in the meantime had altered the direction of their march after the clash with Ziethen and were now headed in the direction of Namslau and Öls (in the area to the east of Breslau) as it made their supply situation rather easier.On 20th July Frederick began the manoeuvres intended to keep the Russians and Austrians apart and to successfully defend Silesia. His intention was to keep a close eye on Laudon as the more dangerous enemy, and to seek a decision if it was necessary or if the opportunity arose only against the Austrians, against the Russians he would remain on the defensive in view of the situation in St. Petersburg and the qualities of their generals. After a series of manoeuvres, the Prussian main army was at Neustadt in Upper Silesia on 31st July, while the main Austrian force was at Jauernig to the east of Glatz. The Russian main body was at Namslau, with a detachment under Czernitschew at Bernstadt to the west.

The Russians now took the decisions that led to their eventually crossing the Oder at Leubus below Breslau. There had been lengthy discussions between the Austrians and Russians durting the march from Posen about where and when they would reach and cross the Oder, questions of supply etc. and there was also a good deal of opposition to the whole idea of uniting with the Austrians among the Russian generals. On 1st August the Russians told the Austrian representative at their headquarters, Caramelli, that a crossing between Brieg and Breslau was too dangerous as Ziethen was standing south of the river, a crossing at Ratibor in Upper Silesia would take too long and endanger the Russian base and supply lines along the Vistula, and so therefore the army would march down the right bank of the river past Breslau and cross between there and Glogau.

On 2nd August the Russian march began, and the troops under Czernitschew arrived outside Breslau on the same day. The main body arrived at Breslau on the 4th. The advance resumed on the 6th, and on the 7th Buturlin stopped at Peterwitz to await the arrival of a huge convoy (it arrived there on the 8th) which would secure the army`s supply up to and including 17th August. The detachment under Generalmajor von Knobloch, which had left the area to join the King`s army on 28th July, returned to Breslau on 6th August and took position on the right bank of the Oder, and a cannonade ensued between them and the Russian rearguard. Buturlin believed that Knobloch was the advance guard of the King`s army, and the plan to cross the Oder at Auras once the supply convoy had arrived seemed risky and he decided to move on to Leubus. The advance guard crossed the river on 10th August.

Laudon was not informed of the Russian decision to move down the Oder until 6th August, and this immediately created difficulties in terms of supply; his organisiation of the supply lines had been carried out on the assumption that the Russians would cross the Oder above Breslau and the two armies unite in Upper Silesia; now the Russians were crossing below Breslau and were asking that he provide supply for them from 18th August.

The Camp of Bunzelwitz

Frederick did not have certain information over the enemy intentions and whereabouts for several days. Initially he concentrated his forces at Strehlen (5th August), then when he had news from the commandant of Schweidnitz that Laudon had arrived at Kunzendorf to the west of the fortress he marched to Canth, reaching it on August 10th. The situation now developed which led to Frederick entrenching himself in the Camp of Bunzelwitz. The Russians crossed the Oder and concentrated their main body at Parchwitz on August 12th. Over the next days the Austrian and Russian armies slowly neared each other; Frederick for a time stood between them, but it became apparent that with his 50,000 men he could not hope to reach a decision against the 130,000-strong enemy; Laudon wanted to attack the Prussians, the Russians were not prepared to do so; however the ring slowly closed around Frederick and beginning on August 21st his troops began building fieldworks. Over the following days Buturlin advanced closer to the Prussians and by August 29th the Prussians were effectively surrounded (but they were able to take supplies from the fortress of Schweidnitz a short distance from the camp). Laudon had now concentrated the great bulk of his forces, 80,600 men with 290 guns, he reconnoitred the Prussian positions on the 29th, and presented his plan of attack to Buturlin, expecting that this time the Russians would agree to a joint attack.

The plan called for 102,500 men to be involved directly in the attack, with a further 37,400 in support, a total of 139,900. The attack was to begin at 3.30am on the morning of September 3rd, in order to conceal the allied approach and to minimise losses from Prussian defensive fire. On September 1st Buturlin asked for changes in the deployment for the attack in certain areas, and subsequently stated that new Prussian fortifications made an attack on the Prussian right wing hopeless; Laudon now accepted that the attack would not take place, and accused Buturlin of missing the opportunity to attack on 27th August when the prospects for success would have been much greater. Buturlin in response declared that the Russian Army was not capable of marching and manoeuvring like the Austrians, and had to settle for defending itself if attacked.

There had been no time for Laudon to arrange a reserve of fodder in the area around Schweidnitz and available supplies were almost exhausted. The Prussians were almost out of fodder, and on the 4th and then again on he 7th of September Frederick had to resort to forced requisitions in settlements to the east of Schweidnitz; Frederick`s communications with Breslau had been cut also, and Laudon hoped that something might be achieved before the Russians left. On the 9th the fodder shortage in the Prussian camp was very seriouis indeed, but on the evening of the 9th the Russian main body broke camp and headed towards Liegnitz. A corps under Czernitschew remained with Laudon in Silesia. Subsequently St. Petersburg expressed regret at the way the campaign had developed (they were unhappy with Buturlins` performance), and Czernitschew was ordered to remain with the Austrians in Silesia and to operate with them. On September 10th Laudon began redeploying to suit the new situation.

Immediately after the departure of Buturlin Frederick sent a detachment of 11,000 men under Generallieutenant von Platen across the Oder at Breslau on a mission disrupt the Russian supply lines so as to forestall any possible move by Buturlin against Brandenburg and Berlin. A detachment destroyed the Russian magazine at Kobylin, and then near Gostyn the Prussians took a large Russian convoy headed for Buturlin`s army. News of this caused Buturlin to immediately set out for Posen. Platen destroyed the limited amount of supplies remaining at Posen and then marched on to Pomerania.

The Prussian main army remained in the camp at Bunzelwitz. Laudon still had a total of 94,300 men available, but did not attack. Thoughts now began to turn elsewhere, and in view of the fact that Frederick would probably want to spend the winter in Saxony with his main army and would therefore leave Bunzelwitz at the final moment before winter closed in, Laudon suggested to Vienna that he could send reinforcements to Saxony in the hope that much of the territory could be taken before winter (Vienna was thinking along the same lines and decided to go ahead with the idea); further troops could be sent from Silesia if Frederick hurried to Saxony in response, and Laudon could then attempt to take one of the Prussian fortresses. The Austrians were preparing to carry out this plan when the situation in Silesia changed suddenly. The army at Bunzelwitz was drawing supplies from Breslau, a procedure which called for strong forces to escort the convoys; these could be ill-spared from Bunzelwitz so Frederick decided to move nearer to Neisse, which had ample stores. At the same time he hoped to draw Laudon away from the areas south and west of Schweidnitz by appearing to threaten an advance into Moravia. This would provide a better basis for his planned march to Saxony for the winter. The Prussians set out on 26th September.

Laudon decided that this Prussian move was a diversion, so he sent a detachment of 9,000 men to join the 4,900 men under Bethlen in Upper Silesia, this force would provide an initial protection for Moravia; meanwhile he had decided not only to stay near Schweidnitz but to take it by an escalade (an attack using ladders to get into a fortress where no breach had been created by artillery fire).

The Storming of Schwiednitz

Plans and preparations for the attack, which was to include Russian troops under Czernitschew, were quickly made.They comprised the carrying out of the actual attack on the fortress, and preparing to cope with a rapid return by Frederick in response to the attack. To cover against Frederick`s return the corps of Feldmarschalleutnant Beck was deployed to Jauer and Klein-Röhrsdorf. The attack on the fortress was to take place on 1st October, and on the evening of September 30th the troops facing Schweidnitz took their tents down and formed up to march to Reichenbach. The movement was actually begun by the cavalry of the right wing. After dark the army returned to camp, with the exception of the troops that would be mounting the attack, although no camp fires were to be lit. At 10am on the morning of the 30th a chain of cavalry and light infantry outposts was set up around the fortress at some distance from it, as darkness fell they moved nearer to it; the intention was to prevent anyone from entering Schweidnitz. Under the protection of these outposts the defensive works were reconnoitred by the officers who were to lead the attack columns. As many ladders as could be found were taken from the surrounding villages (as far as possible discreetly) and collected on the west side of the village of Kunzendorf west of Schweidnitz. Several hundred were brought in. All other matters were regulated by the Disposition setting out the details of the attack, this was based on the knowledge of the works gained during Austrian occupation of the fortress in 1757 and 1758, and also on what was known of the garrison and its security procedures from deserters.Map 1 - Plan of the Fortress amd Points of Attack

Schweidnitz was surrounded by two lines of fortifications. The suburbs of the town were between the two lines and by 1761 had been largely destroyed. The outer line consisted of five linked bastions, namely I. the Galgen-Fort, II. the Striegauer Fort, III. the Garten-Fort, IV. the Bögen-Fort, V. the Wasser-Fort. I-IV. were en tenaille and star-shaped, V. was a hornwork. Each line between the forts had a lunette, except between V. and I. Both the inner and outer circuits were protected by three rows of Wolfsgruben ("Trous de loups", otr "wolf pits"; these were rows of pits up to six feet deep and six feet wide with a stake at the bottom, often they were covered with light hurdles and a thin layer of soil), and in front of them a row of spanische Reiter (chevaux de frise). The garrison consisted of five battalions, a detachment of cavalry, and 300 artillerymen, in all around 4,400 men of whom 4,100 counted as combatants, under the command of Generalmajor von Zastrow. Four battalions held the outer works, the fifth the inner. A total of 339 guns were available, including 36 heavy and 134 light mortars.

The attack was organised accordingly. 20 battalions, 6 grenadier companies and 4 squadrons under Generalfeldwachtmeister Amadei were to attack the four forts and three lunettes of the north, west and south sides, while 3 battalions and 3 grenadier companies under Generalfeldwachtmeister Jahnus would at the same time mount a diversionary attack against the two works on the east side. This would distract the defenders and ease the task of the main attack force. The attacking force totalled 16,000 men and outnumbered the defenders almost four to one.

The following forces were used in the attack columns:

For the attack on the Galgen-Fort (I.) aand Lunette 1.: 5 battalions (1 of grenadiers), 2 grenadier companies, 1 squadron, 10 reserve guns, and 20 gunners who were to man the captured guns; 6 officers, 8 ncos and 140 men to carry 60 ladders, an Arbeiter-Abtheilung (literally "workers detachment") with 3 officers, 5 ncos and 100 men with axes, shovels and pickaxes, and planks to cover the Wolfsgruben (both these detachments to be taken from the battalions in the attack column), a detachment of 1 officer, 2 ncos and 40 Zimmerleute with axes and large hammers, finally 16 Pionniere and 6 Sappeure;

for the attack on the Striegauer Fort (II.) and Lunette 2: 5 battalions ((1 of grenadiers), 1 squadron, 8 resere guns, the rest as for the previous column;

for the attack on the Garten-Fort (III>) and Lunette 3: 5 battalions, 2 grenadier companies, 1 squadron; the rest as for the previous column, except only 10 Pionniere;

for the attack on the Bögen-Fort (IV.): 5 battalions (1 of grenadiers), 2 grenadier companies (Russians), 1 squadron; others as for the first column, except there were no Sappeure.

A further 4 battalions were held in reserve under Laudon`s control.

The diversionary attack on the east side was to be mounted with 2 battalions of Peterwardeiner, 1 battalion of Oguliner, and 1 Grenz-Grenadier-Bataillon with 2 companies of Peterwardeiner and 1 of Oguliner. The main purpose was to keep the defenders of Fort V. and Lunette 4 fully occupied. A part of this force was also to occupy the village of Kletschkau.

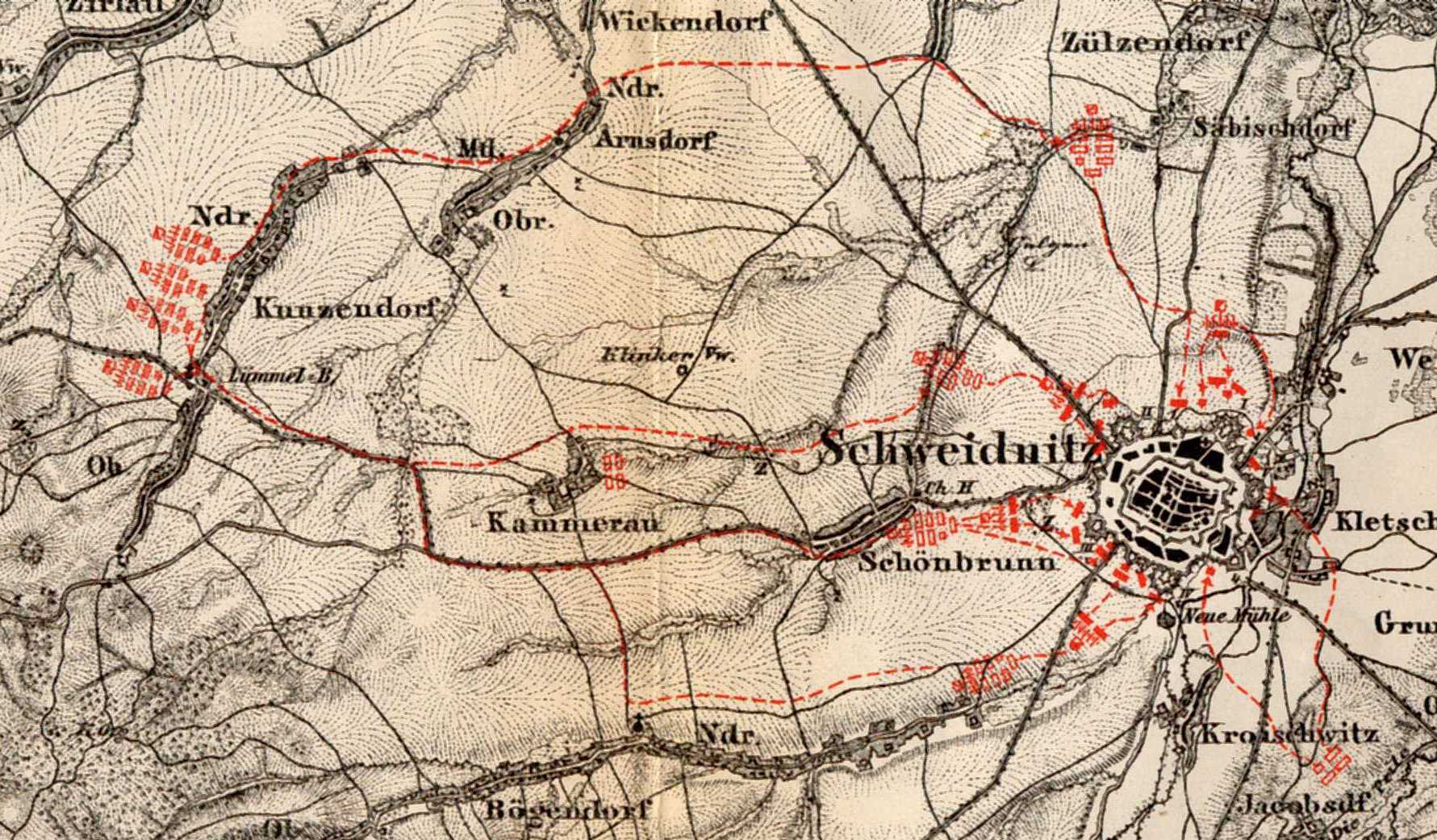

The troops of the four main columns were to assemble at 4pm on 30th September just west of Kunzendorf. The battalions were to have a full complement of officers, the men not to carry packs, the Arbeiter only to carry slung muskets; 100 men from each grenadier battalion were to be issued with two hand grenades each. From here they were to be led to the positions from which the attack would be launched. Map 2 shows the areas where the troops were assembled and from where the attacks were launched, Map 1 shows the points of attack more clearly.

Map 2 - The Attack on Schweidnitz

The 4 battalions in reserve were positioned immediately to the east of Kammerau.

The advance was to begin at 2.30am on the morning of October 1st. There was no signal, instead the commanders of the columns had synchronised their watches. When the columns were 5-600 paces from the works, Laudon was to be informed; after that the columns were to hurry forward without firing and without delay so as to reach the covered way and the ditch as quickly as possible. If the attackers encountered any enemy parties they were to claim they were deserters so as to delay the moment of the attack being discovered for as long as possible.

Each element in the attacking columns had specific tasks at various stages of the assault. The cavalry for example were to maintain order at the rear of the attacking troops, and to take charge of any prisoners taken, then when the attackers had broken into the town inside the inner line of works they were to help deal with any remaining resistance. Once the outer works were secure the troops were to advance and take the inner enceinte.

The Prussians became aware of unusual activity on the Austrian side and at 5pm on September 30th von Zastrow had the various works occupied as follows: Forts II-IV., each with 27 guns, were each held by 270 men; Fort V., with 12 guns, had 50 men. The lunettes, with 8 guns each, were each held by 30 men. Some 450 men were spread along the lines between the works; 1,440 men, in four detachments, were deployed as a reserve behind the outer enceinte. Around 560 men were left for the inner enceinte. Outposts were established on the glacis, and mounted patrols were sent out on the roads to east and west. Despite this the Prussians seem not have been too concerned.

The Attack

The troops assembled at 4pm, and marched out at 9pm. By 2am on the 1st all units were in position without the Prussians having noticed anything. At 2.30am the advance began. The column attacking the Bögen-Fort (IV.) was the first to contact the enemy. It was not one of the Prussian outposts but a sentry at the fort who noticed the Austrian column as it appeared immediately next to the fort. After some resistance the Austrians were on the main wall of the fort by 3.30am. During the action the forts` powder magazine exploded, killing the majority of the defenders and causing some loss to the attackers. The columns approaching Forts II. and III. were observed before they reached the glacis of the forts. The defenders were warned by the cavalry outposts and by the firing from Fort IV. and threw Leuchtballen (literally "light balls", flares) into the approaches, and took the attackers under heavy fire. The Austrians quickly reached the main wall of both forts and by 4am they were taken. The Galgen-Fort (I.) held out longest, the attacking column had the longest distance to cover and the defenders were able to prepare for them. The heavily-outnumbered defenders did eventually succumb, especially after elements of the column which had mounted the diversionary attack from the east joined the assault.

The commander of the column attacking from the east kept Lunette 4 occupied with his grenadier battalion, with his 3 other battalions he initially approached Fort V. the garrison of which had been reinforced by troops driven from other works. His force passed by it to the north, then broke through the wall to its west. Elements of the Gradiskaner attacked Fort I. from the rear, the rest moved on to attack the inner works. The following Peterwardeiner surrounded Fort V. The fall of the fort was certain, but happened sooner than it might have done after some Austrian prisoners being held in the fort broke out and lowered the drawbridge.

While the battle for the forts was still in progress, units which had attacked the lunettes and the curtain moved on to attack the Prussian detachments in reserve behind the outer line. These fled and most were captured before they reached the inner line. The assault on the inner line, like that on the outer, was not simultaneous in all areas. The two Russian grenadier companies were the first into action, climbing over the wall next to the Bögentor (the gate opposite Fort IV.). There was little organised resistance, and the attackers broke into the town and captured Generalmajor von Zastrow. At 5.30am., Schweidnitz was in Austrian hands. Final Prussian resistance came from some of the lunettes which had not been overrun earlier; they surrendered shortly before 6am.

The allied losses were: Austrians 281 killed, 1,036 wounded and 140 wounded; Russian 55 killed, 86 wounded. Total losses 336 killed, 1,122 wounded, 140 missing = 1,598, including 69 officers.The Prussians lost some 1,100 men killed;. 1 general, 121 officers, 2,820 men were captured; 658 wounded (including those wounded in the attack) and ill were also taken. 787 allied prisoners of war were freed. 25 flags, 1 pair of silver and 2 pairs of copper kettle drums were captured. In guns and equipment the allies took 169 cannon, 170 mortars and 4 unusable guns (total 343), 9 gun carriages, 118 wagons, many small arms, large amounts of ammunition, tools, and food supplies, and 38,500 Gulden in Prussian money.

Schweidnitz was immediately given a garrison of 10 battalions and 8 grenadier comnpanies (6,400 men), with 20 battalion guns, under Feldmarscchalleutnant Baron Buttler. Work also began immediately on repairing the fortifications, this was supervised by Generalfeldwachtmeister Gribeauval, and initially 750 men were employed on it daily, later 1,000. Nonetheless the state of the works was such that the fortress was effectively indefensible for some weeks; Laudon estimated that it would be four months before it could be left to stand by itself against an enemy.

The attack on Schweidnitz is a fine example of the kind of detail that went into planning and carrying out operations in this period. Every man knew his place and task, and all eventualities were catered for; such a well-organised operation would always have a good chance of succeeding.

Effects of the taking of Schweidnitz

Frederick the Great was forced to abandon his plan to march to Saxony for the winter. The forces he currently had in Silesia were enough only to protect what he still held, any attempt to retake Schweidnitz would have to wait until Platen returned from Pomerania. However events in Pomerania resulted in Platen not returning to Silesia and the plan had to be abandoned. In addition the loss of Schweidnitz caused something of a shock in the Prussian Army generally. For Laudon the advantages promised by his having taken Schweidnitz would not come into play for a time due to the condition of the fortress. Whereas he earlier wanted to send some troops to reinforce Daun in Saxony, this was now inadvisable as he faced the prospect of an attempt by the Prussians to recover Schweidnitz and this would require all his forces; he also had to ensure the protection of Moravia against a possible enemy advance. But he was then ordered by Vienna to send strong forces to Daun (almost 30,000 men) and thus when his troops went into winter quarters at the beginning of December he had a total of 66,000 men (including the Russians), and a garrison of 5,900 in Schweidnitz (there were claims at the time that he could have been more active against Frederick after he had taken Schweidnitz; this perhaps is an example of the fear and uncertainty that Frederick inspired in his opponents throughout the Seven Years War). Frederick had received bad news from Pomerania in November and had been obliged to detach a part of his army to send there; thus when he went into winter quarters he had some 38,000 men remaining. For the first time the Auustrians had aquired a secure foothold in Silesia that would allow them to hold part of the province over the winter, which meant loss of revenue and resources to the Prussians. In Saxony the Prussians had lost ground also; Pomerania was lost to the Russians (Colberg had finally fallen on 16th December; and William Pitt would not be Prime Minister in 1762, which would mean the end of the British subsidies. But then on January 5th the Empress Elizabeth died at St. Petersburg, and Russia withdrew from the war shortly after; and so Frederick eventually retained Silesia.Had Laudon been able to carry out his planned attack on the Prussians at Bunzelwitz, it would almost certainly have been the end for Frederick and his army. But then as one Austrian source puts it, the attitude adopted by Field-Marshal Buturlin, from the time he marched from Posen in June until he recrossed the Oder in September, seemed suited to the process of preventing any undertaking, whether large or small, from becoming a success. Against this there is the storming of Schweidnitz, a project which was decided on, planned and carried out within the space of forty eight hours.

Website "The Seven Years war 1756-63"

©Martin Tomczak 2003